Some of my first days in the year of 2016 were spent in Cuernavaca, Mexico with a group of students from Oakland, some students from other U.S. cities and a group of teachers, activists and community members from Mexico. We all came together at CETLALIC: CEntro TLAhuica de Lenguas e Intercambio Cultural (Tlahuica Center of Language and Cultural Exchange) where we had the opportunity to learn from activists and community members from Mexico and around the world.

I interacted with so many people within those two weeks, and each shared with me

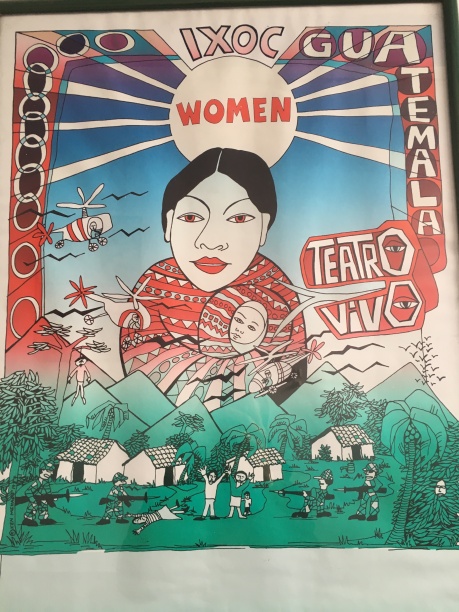

something from their experience. The experiences that people shared with me brought me closer to understanding situations that I would never experience first-hand. They helped me see the complexities of situations that my privilege enabled me to overlook. Kaniya, my classmate from Mills who made the 30 minute bus ride with me to class every morning, shared her experiences of travelling as a Black woman in Mexico and Puerto Rico. Delmis, the woman in the market told me about fighting for the survival of her family and neighbors in the civil war in Guatemala for years before seeking political asylum in Mexico. Trini, my host, who opened up her home to me, fed me generous helpings of cafe, quesadillas, and stories about her experiences fighting for political participation and equal access to resources for women and lesbian, gay and transgender Mexicans.

I’m always thinking a lot about relationships between myself and the people I encounter. A question that I kept asking myself was: how can I practice solidarity with the people I’m meeting here in Mexico? I thought about the ideas of “common differences” and transnational feminist solidarity that I was introduced to through the writings of feminist theorist and activist scholar Chandra Talpade Mohanty. She writes about how paying special attention to our differences as women in different contexts allows us to understand how our positions are connected. It is through these differences and the connections they expose, that we can find our common concerns and interests, and it is through our common interests, that we can build solidarity. In thinking about Mohanty’s writings I also thought about the importance of being in solidarity with people in my own neighborhood, city and country . Mohanty taught me to see the ways that we use borders and nations to ignore the ways that people are suffering, not only in “other” countries, but in our own cities as well.

So what exactly is solidarity?

This is a question that I continue to grapple with every day. Mohanty defines solidarity “in terms of mutuality, accountability, and the recognition of common interests as the basis for relationships among diverse communities” She states that diversity and difference are key values that must be centered and respected in order to work together in active struggle.

Two key things that I find useful in this definition are the idea of common interests and active struggle. The viewpoint of common interests is what is missing from ideas of charity and allyship. Both charity and allyship approach activism from a framework of sympathy and paternalism. They say “I have something you don’t, so I’m going to share it with you,” or “I am going to do this for you because I care, not because I have to”. These frameworks always highlight the morality of the giver or the ally. The framework of solidarity, however, says “I want to join you in working towards this goal because I see that it’s beneficial to all of us” and “I see our wellbeings as connected”

During my time in Mexico, The extreme violence that accompanied every mention of Mexico in the news was not the reality that I experienced. I felt safe. I was well-fed and treated with immense kindness by acquaintances and strangers as I made my way through the city, exploring different museums, parks and restaurants. Even when I missed my bus stop heading home at night and got lost, a stranger helped me find my way back to my homestay.

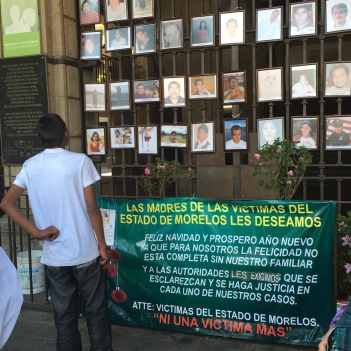

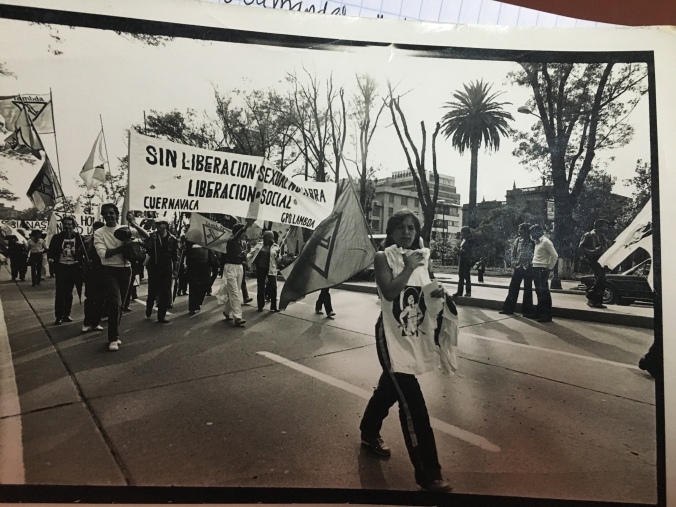

However, while white tourists are well cared for and protected from harm, I learned that other people were not so safe. I learned about how the government uses violent repression to silence activism. I learned about the ways that free trade agreements made it impossible for mexican farmers, manufacturers and business owners to make a living, impoverishing entire communities of people. I saw graffiti all over the city walls that read “Todavia nos faltan los 43” (we’re still missing 43) and “narcogobierno” (narco-government) talking about the 43 students that were stolen

by the government and how the government and the drug traffickers are one in the same, wreaking violence upon communities. I learned a

bout how racism and classism continue to invisibilize and impoverish indigenous communities and that it wasn’t until last year that Afro-Mexicanos were even recognized by the Mexican census.

But these atrocities don’t go unaddressed. The people I met are engaged in resistance. I saw Trini, my host mom, tired after spending her days in meetings with activists and government officials to address the assassination of one of the first women to be Mayor in one of the neighboring towns. I saw Martha and Jorge the founders of the school working tirelessly to raise funding to keep the school going, connecting with community activists to build support, all while welcoming each one of their students, teachers and staff as if we were all family.

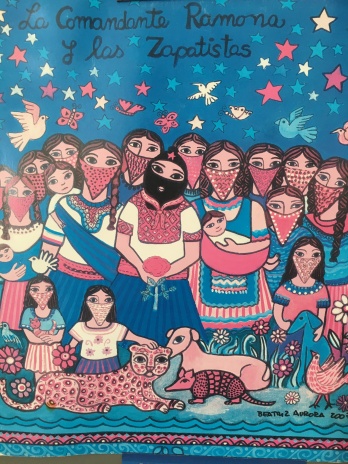

I learned about the the Zapatistas, indigenous resistance fighters, living in Chiapas, restoring self-sustained communities while defending their land from the Mexican government who continues to attack them. I met Francisco, who helped organize the first gay pride parade in Cuernavaca 11 years ago. I saw the teachers and activists who openly shared their knowledge and experiences with us, so we could better understand the conditions of their lives. So many people are working, fighting against the forces that seek to silence them, and building strong communities that care for each other

I came to Mexico wanting to learn more about building solidarity across national borders. In getting to know so many people, and seeing first hand the work that they do in their communities, the question continued to arise in my mind: How can I be in solidarity? I thought a lot about my own identity and position and I saw the ways that I experienced a lot of privilege. So what is my place in all of this?

One thing that kept coming up during the trip was the exchange rate of the U.S. Dollar and the Mexican Peso. During my time there, it was around 18 pesos to the dollar. Yet many goods, like gasoline were imported from the U.S. at U.S. prices. We learned how the devaluation of the peso was largely due to the effects Free Trade Agreements. Although I didn’t have much money in the U.S. in Mexico, I felt rich. This experience really showed me the power of spending. Because my money was worth so much more in Mexico, I had the opportunity to act in solidarity through the choices I made about spending my money. I tried to be conscious about supporting local merchants instead of corporate chains and big box stores.

One thing that kept coming up during the trip was the exchange rate of the U.S. Dollar and the Mexican Peso. During my time there, it was around 18 pesos to the dollar. Yet many goods, like gasoline were imported from the U.S. at U.S. prices. We learned how the devaluation of the peso was largely due to the effects Free Trade Agreements. Although I didn’t have much money in the U.S. in Mexico, I felt rich. This experience really showed me the power of spending. Because my money was worth so much more in Mexico, I had the opportunity to act in solidarity through the choices I made about spending my money. I tried to be conscious about supporting local merchants instead of corporate chains and big box stores.

Some basic guidelines for my practice of solidarity:

Who am I acting in solidarity with? In order to act in ways that are accountable it is important to build relationships with the people and communities that you are acting with. What does that look like? Well, relationships are always different depending on the two people who are involved. Some things that I’ve practiced in order to show my commitment to a group of people is showing up consistently to support the projects, actions and efforts of that community. Being patient because people don’t always trust me right away, and understanding that relationships take time.

Some questions I ask myself when I am attempting solidarity:

- What are the circumstances/what is the context?

- What are the possible outcomes of my action?

- How will my actions benefit those I am striving to act in solidarity with?

- How are my actions accountable to the people and communities I am seeking solidarity with?

Pay attention. Having multiple intersecting privileges means that my experiences are often made to seem like “the norm”. This means that it may not always seem obvious to me the ways that other people are experiencing the world. By paying close attention to the people and world around me I can be more aware of the ways that other people experience the world and are treated by it. This can inform my behavior to be more considerate of other’s experiences, as opposed to just acting based on my own experience.

Being called out is a gift. If someone calls me out my goal is to react by listening, apologizing, and then changing my behavior. Being called out means that someone took the time and energy to inform me that my behavior is harmful, which for someone who has experienced repeated harm, can be difficult– and I appreciate that. I need to honor their efforts.

Listen…Actively (Self-Education). I practice listening to what people tell me without defensiveness or immediate judgement or even critical analysis (which is hard because I like to critically analyze everything). Just listen. With an open mind and an open heart. But just listening to the voices that are readily available is not nearly enough because systems that work to oppress people do so partially by silencing voices, erasing histories, denying access. In her essay The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action, Audre Lorde addressed white feminists demanding that, “where the words of women are crying to be heard, we must each of us recognize our responsibility to seek those words out, to read them and share them and examine them in their pertinence to our lives.” I understand this as a demand to seek out the voices that are most silenced. Only when we hear those voices, can we be truly informed about how to act. “And there are so many silences to be broken” (Lorde)

Solidarity is a process and a work in progress.

Attempting solidarity can be messy and ugly and I know I don’t always do it right. But I won’t stop trying because I understand people as being connected. How and when I use my voice, where I spend my money, how I interact with people and communities (my own and those that I’m not a part of), all have effects on other people’s lives. Every day I am learning more about how my actions are connected to communities and people around the globe, and in my own town, who I will never meet. Everyday I’m learning about the ways that the well being of people across town, across borders and across oceans are connected to my own. I know that my actions alone will not dismantle systems of oppression or build communities of love and accountability, but every day I make choices and I want to pay attention to those choices and be accountable in my actions.

A bit about the author:

I’m a white, middle-class, Jewish, queer, U.S. born person. I love cooking, sharing meals, connecting with people, learning about community building and systems of oppression, and riding my bike.

RESOURCES: If you’re interested in learning more about CETLALIC, activism, solidarity and more, below are some resources I’ve found extremely useful.

- http://www.cetlalic.org.mx CETLALIC

- http://www.blackgirldangerous.org/2013/09/no-more-allies/ Black Girl Dangerous-Mia McKenzie

- https://www.csusm.edu/sjs/documents/silenceintoaction.pdf Audre Lorde: The Transformation of Silence Into Language and Action

- http://www.blackgirldangerous.org/2015/11/the-difference-between-real-solidarity-and-ally-theatre/ Black Girl Dangerous-Mia McKenzie

- http://www.thenation.com/article/how-desaparecidos-ayotzinapa-have-sparked-us-mexican-solidarity-movement/ This article is about the mobilization of students in the US around the 43 missing students of Ayotzinapa. It is one example of US students practicing transnational solidarity:

- https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/allyship/ This is a website of a decentralized network of people who are dedicated to decolonization. This website documents the various projects and work of the people and groups that make up this network and offers multiple resources (guidelines, videos, etc) about general solidarity and allyship with decolonizing efforts and indigenous peoples, and specific resources about solidarity with specific projects.

- http://sexualidadescampesinas.ucdavis.edu/en/about-the-project/ This is a digital storytelling participatory research project about diverse sexual and gender identities members of farmworking communities in California, conducted by a student at UC Davis. This is an example of students practicing solidarity through research.

- http://bdsmovement.net/bdsintro#sthash.Bok9qI7y.dpuf http://bdsmovement.net/bdsintro BDS is a strategy that allows people of conscience to play an effective role in the Palestinian struggle for justice.

- http://www.soaw.org/resources/anti-opp-resources/108-race/484%20 An article by Chris Crass, a white activist, reflecting on white supremacy and solidarity.

- http://www.alternet.org/civil-liberties/10-things-everyone-should-know-about-white-supremacy Ten Things Everyone Should Know about White Supremacy

- http://www.unm.edu/~unmsc/Documents/Feminism%20Without%20Borders.pdf Chandra Talpade Mohanty: Feminism Without Borders, introduction and Chapter One (Under Western Eyes)